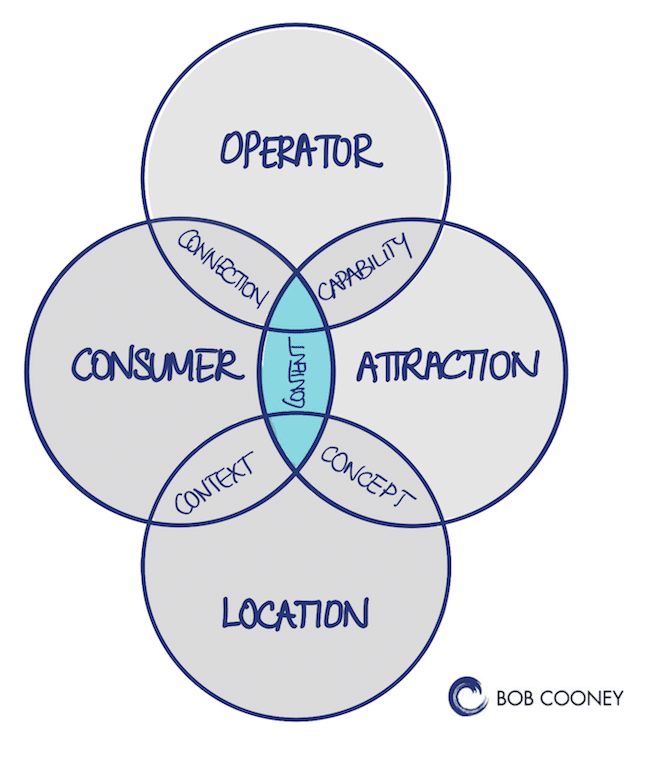

For the last couple of months, I have been writing about how to select the perfect VR attraction for your location-based entertainment operation. I’ve been encouraging operators to take a 360-degree approach, considering things like mindset, staff capability, physical attributes of your location, and the context of the consumer.

At the center of all of these things is the content. One of the great things about VR, when compared to most other attractions, is that the content is flexible. Most VR products today are platforms that can switch content easily and frequently to meet a variety of guest desires.

The variety of content available in VR is already quite broad, but it will soon become staggeringly so. With tools like Unity, creating VR experiences is becoming something almost anyone with basic programming skills can do. This has become a problem for the location-based entertainment market. There are so many products flooding the market, how can an operator know what’s good and what isn’t?

Too many people focus on the quality of the graphics. While graphic quality is certainly something to consider, some of the best games of all time have used low polygon or even vector graphics. Minecraft is an excellent example of the former, using crude graphics that look like they’re right out of a 1980’s arcade cabinet.

One of the most popular VR arcade games is Super Hot, which is overly simplistic in its graphic design. Unfortunately, most developers are making up for lack of game quality with beautiful environments, which, when displayed in VR, are stunning to view. However, once the novelty of the graphics wears off, one is left with a game that can be boring, repetitive, and with no replay value.

It seems like anyone who has ever played a game thinks they can design one. There is a job title of Game Designer, and very few of the companies that I have spoken to in the game design business employ one. Game designers are math nerds. They know how to create compulsion loops, balance weapons, and enemies, and make sure that players of all skills have a consistent experience across all levels of the game. There’s a great book called The Theory of Fun, but legendary game designer Raph Koster. You can get it here on Amazon; it provides a fascinating look at how game designers create fun experiences.

When evaluating a VR game, here are some things beyond just graphics that you might want to consider:

In games that have enemies, variety is essential. How many enemies are there, and do they have different attributes that require a different strategy to defeat? Too many games employ multiple enemies, but they’re mostly the same under the skin. Just because I need to shoot one five times and another ten doesn’t create gameplay variety.

Does the game offer different control mechanisms? If it’s a shooter, this can be a variety of weapons. If it’s an exploration game, it might be various tools like a flashlight, a pickaxe, and a book of matches. While variety is critical, ease of use is more so. Is the control schema intuitive, or does it require you to think? If the latter, it will break immersion and take people out of the experience. Long tutorials at the beginning of a game are useless. People don’t pay attention and cannot remember what they’re told. Great games educate the player while they’re playing. They start with one weapon, then let them discover additional ones, and instruct them the very first time they use it.

This takes me to the First-Time User Experience, or FTUE (say Fatooey). Not enough games take the first time user into account. The games are designed and tested by the programmers. They are intimately familiar with the game and the way it plays. The deeper they get into the development process, the more expert they’ve become at the game mechanics. This makes them unqualified to test the games for playability. Most studios employ little to no consumer testing, and when the games get to market, they can be incomprehensible to the first-time player. A good FTUE can drive higher replay rates, because if the player has fun the first time they are more likely to play a second, and third. If their first experience is frustrating, then you’ve lost them forever.

In arcade games, you can usually accelerate your way past these if you’re an experienced player. With multiplayer VR games, it’s more difficult, as it becomes more likely that someone will be a first-time player. Making the FTUE fun for everyone eliminates the boredom for the more senior player. This is why tutorials and instructional videos are frowned upon and are a lazy way to teach players how to play a game.

Once the game starts, what’s the pace of action like? Great games, like movies, have ebbs and flows in the intensity and pace. Cutscenes are used to tell the story and give players a breather. Boss battles are often employed to give a game a sense of peak conflict and then resolution. Games that do not pace the action can feel repetitive and boring, even if the action is non-stop.

I interviewed game designer Joe Mares on my Deep Dive Webinar recently, and he said that fun is a combination of surprise and delight. How many times when playing the game were you surprised and delighted? Did it keep happening all the way until the end? A great game will spread out the surprises through the entire gaming experience, and layer them, so players continue to discover new things as they improve. This is one of the critical components of a highly replayable game.

Another thing I notice missing in many games is clear feedback. This is critical, especially in VR, where the action can be taking place behind the player. If you’re getting hit in the back, do you know it? Some attractions are using vibrating vests. Using haptics is an excellent way of giving players feedback, but if the input is constant and overwhelming, players tune it out, and it can become annoying. The best systems make sure that the feedback is used to inform the player, and to create peak moments in the experience.

Another form of feedback is celebration, or what game designers call juiciness. When you accomplish a goal in a game, does it make you feel like you really accomplished something? One of the things I loved about Chaos Jump is at the end all the guns turn into confetti cannons, and everybody shoots confetti at each other. It’s a great example of a juicy celebration that leaves players with a feeling of accomplishment and lighthearted fun.

It’s been well documented that people want social experiences in VR. Multiplayer games can create a social experience, but only if the players are interacting with one another in the game. There are many multiplayer VR games where it’s almost like each player is playing their own game. If there’s no co-operation or competition, it’s not a multiplayer game. The worst are the games where you cannot even see the other players because the designer has put them back-to-back, and all the action takes place on the outside of the play space.

Most location-based VR systems are operating with a closed content model. The solution provider has a walled-garden for their content, and operators are locked into whatever content that company decides to make available. If they’re great at making games and have the bandwidth to create enough quality games to satisfy the market, then this might be OK.

Other companies are incorporating the ability to add games from the massive library on STEAM or via arcade platforms like Springboard. Depending on the configuration of the hardware, this could be an excellent safety valve for operators who don’t want to be locked into a closed content system.

The next time you evaluate a virtual reality game platform for your location, these are some of the things to consider. Next week I will talk about how to assess non-gaming content.