Last week I wrote about how the attributes of your location can help inform the virtual reality attraction your select. I covered VR Arcades, Family Entertainment Centers, and Trampoline parks. This week I continue this thinking and include Theme Parks, Shopping Centers, and Casinos.  Theme Parks were early adopters of VR despite the inherent throughput limitations of the technology. VR Coaster, a division of Mack Rides, was the first to roll out a system with a great value proposition: upgrade your old, depreciated coaster to a modern attraction and continue to change the experience with software.

Theme Parks were early adopters of VR despite the inherent throughput limitations of the technology. VR Coaster, a division of Mack Rides, was the first to roll out a system with a great value proposition: upgrade your old, depreciated coaster to a modern attraction and continue to change the experience with software.

At last count, there were nearly fifty coasters fitted with VR upgrades since late 2015. Almost all have made VR optional for the guest. VR Coaster did the vast majority, and most are still operating. A few notables have removed VR however, including the Kraken Unleashed at Sea World Orlando, after long lines, technical challenges, and poor guest reviews. The strain on their staff of running a high-volume ride combined with customer frustration of long lines offset whatever novelty factor virtual reality offered.

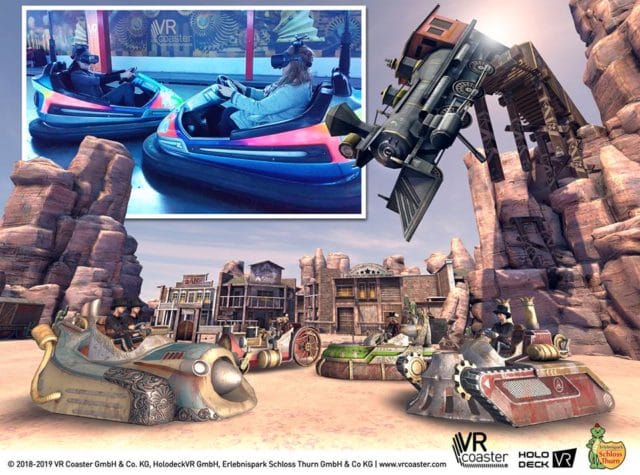

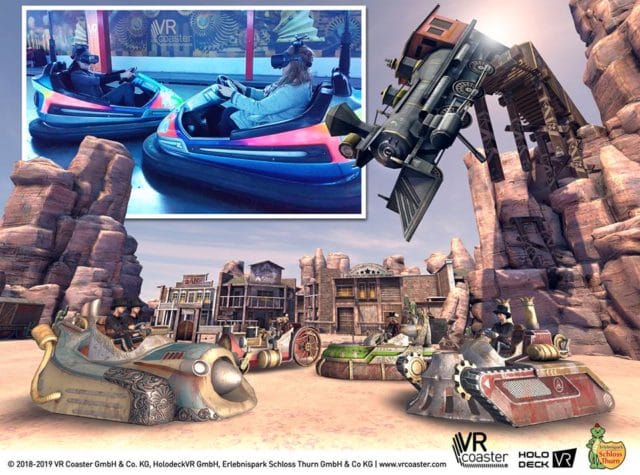

Europa-Park, owned by the Mack Family, unveiled a first last year called Roam and Ride, a joint effort between VR Coaster and Holodeck VR, where players don VR headgear in the queue and enter an immersive free roam pre-show. They remain in the virtual environment as they board the coaster. They based the entire experience on Valerian and the Galaxy of a Thousand Planets from visionary director Luc Besson. The ride has met with rave reviews.

Another concept just unveiled from the collaboration of VR Coaster and Holodeck VR is a virtual bumper car ride. Riders immerse themselves in a cyberpunk world where they get to drive up walls and ride across a computer-generated landscape with their friends. We will see more classic rides updated with new Virtual Reality in the coming years as patrons continue to expect more immersive experiences.  The concept of moving from one experience to another while staying immersed is the future of theme parks. Imagine driving across the Tatooine desert in your land speeder (a bumper car), strolling into Chalmun’s Cantina to take in some alien jazz, battle stormtroopers in Mos Eisley (in a free-roam VR game) and then narrowly escape the Empire’s grasp on the Millennium Falcon (a VR roller coaster).

The concept of moving from one experience to another while staying immersed is the future of theme parks. Imagine driving across the Tatooine desert in your land speeder (a bumper car), strolling into Chalmun’s Cantina to take in some alien jazz, battle stormtroopers in Mos Eisley (in a free-roam VR game) and then narrowly escape the Empire’s grasp on the Millennium Falcon (a VR roller coaster).

The rap against VR in theme parks is the low throughput, but higher prices can offset that. Disneyland demonstrates this with their new lightsaber crafting experience at Sami’s Workshop. Only 14 guests can participate at a time. At four groups an hour throughput is limited to about 720 per day compared to almost 20,000 for Millennium Falcon: Smugglers Run. The experience costs $225, including tax, which is double the price of the admission ticket to the park. Sure, the guests get a souvenir, but even the most expensive lightsabers at the high-end boutique Dock-Ondar’s Den of Antiquities are under a hundred bucks.

Another glimpse that Disney “gets it” is their under-construction Star Wars Themed hotel. The nerds at The Points Guy used their knowledge of hotels and permit applications to determine the hotel might only have around 100 rooms. For a resort that sees more than 10 million guests per year, and typically charges $600 per room for resorts that have between 600 and 2000 rooms, you can imagine what they’re prepared to charge for this.

Shopping Centers are looking to add VR attractions to drive traffic and remain relevant. The paradox is that VR is generally a low-traffic business. Some operators have been able to negotiate rock-bottom rental rates from landlords of distressed properties, but higher-end centers are still demanding rents that undermine the business models of location-based VR businesses.

The VOID operated a pop-up in Westfield London during the Star Wars Episode 8 release last year and found that 70% of the people who purchased tickets had never been to the mall before. This new traffic is excellent for the mall developer, but it hardly makes it worth the exorbitant rent required. Since VR is mostly a destination business and stands to bring in millennial customers eschewing bricks and mortar for online shopping, real-estate developers need to shift their perspective on how to do deals that make sense for everyone.

Too many developers seem stuck in the 1990s where anchor tenants took huge footprints and low rents and drove traffic into the mall, which fed customers to smaller tenants. Today those tenants are like boat anchors, and the smaller local businesses are driving traffic.

I saw this play out in the 1990s when Edison Brothers, then the largest tenant of mall real estate in the US with over 1000 retail stores under brands such as J.Riggings, Wild Pair and OakTree, started a mall entertainment division. Mall operators were begging them to fill their rapidly declining malls with what they called anchor entertainment centers. Soon I was building Laser Storm arenas with Virtuality VR pods in malls across the country.

Edison Brothers mall FEC’s were taking up large footprints and driving traffic. Today’s VR businesses are small and generate relatively small amounts of customer traffic. They cannot drive the number of visits that a large FEC can. A new business model needs to emerge if shopping centers want to play in the VR game, and leverage the cool factor and buzz that comes with hosting businesses like Dreamscape, The VOID, Nomadic or Zero Latency.

Meyden One, which will soon become the third mega mall in Dubai, has announced an incubation district. The three-phase program offers new brands, competitive leasing incentives, positioning, and mentoring. Companies that succeed can move to more premium space in the shopping center and have a platform for global growth.

Progressive FEC operators know they need to give emerging attractions a chance and offer their locations as test beds for experience developers to test their solutions. Shopping Center developers need to take this same attitude. Their survival depends on innovative startups, and choking them with high rents in a business-as-usual leasing model is short-sighted.

Casinos have been dabbling with VR lately with varying levels of success. Like Shopping Centers, they’re fighting for relevance among a generation of millennials who are not interested in gambling. The current generations are the most fiscally conservative of the last century, having grown up in the global financial crisis. Acres of slot and poker machines sit idle at casinos, while Millennials crowd into mega clubs like Hakkasan and Omni in Las Vegas, both which boast top tier DJs like Calvin Harris and Tiesto.

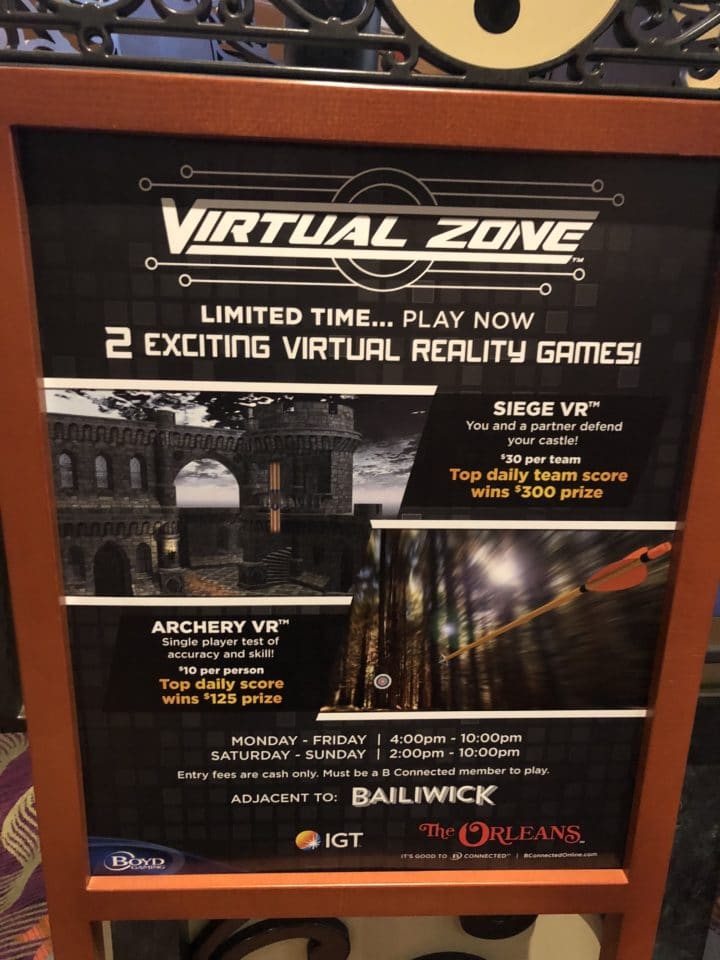

Global slot manufacture IGT recently concluded a test at the Orleans Casino in Las Vegas. Partnering with VR infrastructure provider Exit Reality, they installed a 2-player HTC Vive-based arcade game, encouraging players to enter a tournament. Players needed to join the “slot club” to be eligible, which required standing in a line at the service counter. Considering their target audience didn’t play slots, not surprisingly, it failed.

MGM Grand partnered with Zero Latency to build a free-roam virtual reality center at their Level Up Lounge at their flagship resort on the Vegas Strip. A joint-venture with Hakkasan Group, Level Up was supposed to be a prototype of the casino of the future. It mixes classic arcade games, a bar, a mini-bowling alley and some skill-based gaming machines on test. While Zero Latency has succeeded, Level Up is just an arcade with a bar. Skill-based gaming is still not catching on.

The latest to throw some VR spaghetti at the wall is Caesars Resorts, who has partnered with Survios, the VR game developer out of Los Angeles. In another casino-of-the-future trial, eight room-scale HTC-Vive stations sit unplayed next to a new sports lounge and some Mario Kart arcade game. Around the corner, buried next to the bathrooms is an esports lounge with about 20 PC gaming stations. It’s just opened, but I cannot imagine it will work.

The casino industry is among the worst I have seen at implementing virtual reality. The only success has come through their real-estate leasing arms, where The VOID have opened up a storefront in the mall at The Venetian, and smaller operators are running pop-up attractions in high-traffic corridors.

Their attempts to integrate VR into the on-premise consumer experience has been reactive, experimental, and entirely non-strategic. Products that incorporate tournaments and head-to-head competition make more sense here. The Virtuix OmniArena and Neurogaming’s Polygon, when wrapped around an esports tournament with cash prizes, a bar with high-end spectator experiences, would likely attract an audience on the casino floor.

Part of the problem is the general managers of the casinos still value square footage of the slot floor based upon gaming revenue. However, even a farm animal could tell they could remove 25 games (or 100), and the total coin-drop would not change an iota. In the last two years, I’ve spent countless hours watching slot play and have never seen even 10% of the games occupied at one time.

If casino’s want to use VR to stay relevant and attract a new demographic, they need to be more strategic and consider the context of the consumer, and what might make sense when at their property. However, that’s the subject of the next blog.