Bill Gates coined the phrase Content is King in a 1996 essay posted on the Microsoft website. He predicted that the internet would become a medium for delivering content, much like broadcasting had. He was correct. Today, YouTube has the biggest audience of television watchers—more than any network or platform. And that’s just people watching YouTube on television. It doesn’t include phones, laptops, or tablets.

In the world of downloadable attractions and location-based entertainment, I’m not sure content is king yet.

I still see experiences filled with incomprehensible content and broken interactions garnering Google reviews as high as 4.9. While Google ratings aren’t an indicator of profitability, they do suggest that audiences are remarkably tolerant. What those reviews don’t tell you is whether enough people are showing up every week, paying enough per ticket, to make the venue viable.

So while content may or may not be king in this space in 2026, it is undeniably a pillar of success. And when the conversation turns to content, it almost always ends up at IP.

We are firmly in the age of IP everything.

From McDonald’s Happy Meals to immersive Monopoly experiences in London, IP has moved beyond the screen and into physical space. Mattel and Hasbro are licensing toys and board games to operators. Books like Bridgerton and A Court of Thorns and Roses are being discussed alongside movie franchises. Even fast food has become experiential—ChainFEST reimagines brands like Taco Bell and Pizza Hut as culinary events.

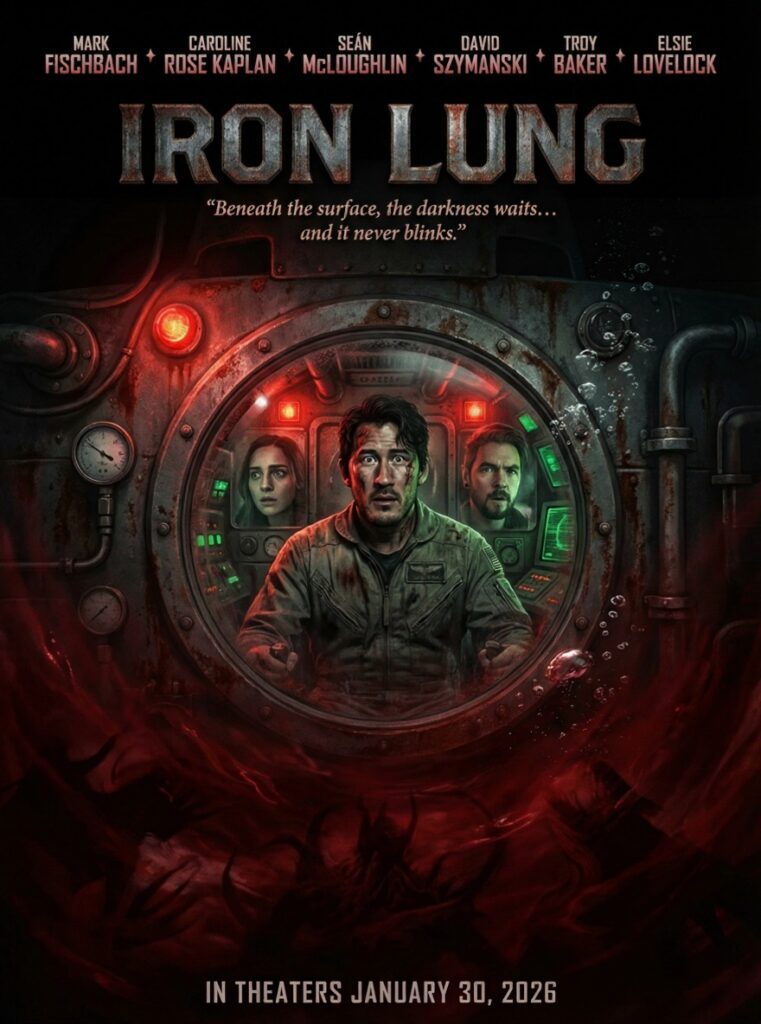

Because IP is everywhere, this should be a buyer’s market. There’s an all-you-can-eat buffet of licensable content: streaming services competing for relevance, video games chasing new revenue streams, toy companies reinventing themselves, and influencers turning audiences into brands. Just this past week, YouTuber Markiplier released his horror film, Iron Lung, to a $21 million opening weekend on a $3 million budget.

Matching IP to the audience should be easy. Negotiating fair deals should be easier. Making money should be easy.

None of this is easy.

Most IP holders wildly overvalue their brands.

They negotiate as if they alone hold the keys to success, while systematically undervaluing the contributions of experience designers and operators. Worse, they often exert excessive creative control despite having no operational understanding of location-based entertainment.

This imbalance doesn’t just drag out deals. It actively damages licensees. IP owners need to stay in their lane. Sure, they must protect the “asset.” But doesn’t a failed product or experience do just as much, if not more, damage to the brand than if the logo is one shade off the style guide?

When VRsenal created Star Wars: Lightsaber Dojo, ILMxLAB—the immersive arm of Lucasfilm—insisted on mechanics that almost guaranteed market failure. They required players to learn force-grab mechanics rather than handing them a blaster or a lightsaber immediately.

That might make sense narratively, and would have worked in a home game where players have already committed to buying and expect to spend hours playing. It makes no sense in an arcade where a game lasts 3-minutes and replayability is measured in fun-per-second.

Arcade experiences live or die on instant comprehension, short learning curves, and repeatability. ILM-XLAB couldn’t or wouldn’t hear that. The result was an expensive product that underperformed unlicensed, lower-priced products.

This is what happens when IP-centricity overwhelms subject-matter expertise.

Sony’s Wonderverse is a textbook example of IP being treated as a substitute for experience design.

The assumption was simple: if you put Ghostbusters, Jumanji, Uncharted, Bad Boys, and Zombieland under one roof, people will come. So Sony skipped customer research, ignored format constraints, and layered IP on top of commodity attractions that had existed elsewhere for years.

They crashed and burned harder than a rookie driver in a Gran Turismo movie.

Netflix took the opposite approach.

Their partnership with Sandbox VR works because Squid Game was adapted into mini-games that respected both the IP and the medium. Stranger Things launched in alignment with the series finale, lowering acquisition costs and giving fans a reason to show up physically.

So, done right, IP always makes sense, right?

Sandbox VR’s biggest revenue driver isn’t Netflix IP. It’s their own Deadwood zombie franchise. Zero Latency sees the same pattern with its Outbreak series, outearning both Ubisoft’s Far Cry and Games Workshop’s Warhammer licenses on its platforms (according to operators).

So maybe a zombie-based IP is the holy grail? VRsenal’s Zombieland, based on the hit Sony movie franchise, failed because the brand couldn’t overcome clunky gameplay and a poorly adapted arcade conversion from the PC game.

IP can’t cover up bad design or a lack of go-to-market execution. Because the reality is that original content pays the bills. If used properly, IP can and should be part of a content library. But it’s the library that matters, not the IP.

The McKinsey When IP Goes IRL report correctly frames location-based experiences as relationship infrastructure rather than just revenue generators.

Theme parks can reach EBITDA margins of roughly 30–40 percent. Family entertainment centers land closer to 25–30 percent. Smaller, short-term LBE formats tend to run thinner, though outcomes vary widely.

Gen Z is 1.5 times more likely than the general population to visit immersive experiences—and four times more likely than older generations. Location-based experiences allow brands to connect with their most engaged fans, who are often significantly more valuable over time.

Where it becomes dangerous is assuming IP alone creates that relationship, and letting the licensor dictate the terms, especially when they show no sensitivity to the challenges of running a retail entertainment business.

There is a temporary opportunity created by underutilized spaces in the retail landscape.

Movie theaters with excess screens. Casinos with dead zones. Malls are searching for relevance in an age when trends shift faster than a TikTok feed. A hot IP can unlock premium space and better real estate economics for operators. I spoke to one multi-unit Sandbox VR franchisee about their ability to negotiate with mall owners. He said landlords love the Sandbox brand, which is built in large part upon its relationship with Netflix. His company is getting significant tenant improvement allowances, which rapidly accelerate his return on capital invested.

Netflix House versus Wonderverse is a go-to-market story, not an IP story.

Timing, promotion, format choice, and audience clarity matter more than brand recognition. Netflix House (and let’s be clear, we won’t be able to declare it a success for at least 2-more years) is designed as an experience platform. They architected their experiences to be rotated between locations at least annually to drive repeat visitation in each market. Where most family entertainment centers keep the same attraction mix for a decade or more, Netflix sees attractions aging in calendar quarters, not years.

In 1995, under license from Studio Canal+, I launched Stargate: The Laser Adventures, which quickly became the most successful laser tag attraction in America (by ROI). So, two years later, under license from Marvel, we built X-Men: The Danger Room. We overshot the market on both complexity and price. And we failed. The product was amazing, but the go-to-market sucked. (In all fairness, younger Bob didn’t even understand what a go-to-market strategy was back then.)

So if you’re an operator or developer and are thinking about pitching or evaluating IP-driven experiences:

And if you’re an IP-holder looking to license into this space, take the time to understand the unit economics of the retail business, as well as the economics of the various participants in the ecosystem. Want help, just HMU. I have a one-day ecosystem mapping workshop that will clarify everything. If you want to help build a thriving immersive LBE industry, it can’t happen if you’re just milking what you can out of every deal.

Because IP isn’t king in location-based entertainment. Execution is.